Definition

- Interstitial lung diseases (ILD) are a heterogeneous group of lung parenchymal disorders, which are classified together because of common clinical, radiologic, physiologic, and pathologic features.

Clinical Presentation

- Symptoms: progressive dyspnea with chronic, nonproductive cough. Ask about extra-pulmonary symptoms (joint pain and stiffness, skin changes, fevers, rashes, etc.).

- Signs: fine inspiratory (often bibasilar) rales (akin to the sound of velcro). Look for extra-pulmonary manifestations (synovitis, rash, clubbing).

Evaluation

- History must include: occupation (going back many years), hobbies, pets (birds), other exposures (mold, beryllium, down), drug history, smoking history, and rheumatologic review of systems. Proceed with CXR, pulmonary function testing, and HRCT. Discuss with Chest Radiology colleagues for any classic/characteristic patterns. Then, proceed as follows:

- Highly suggestive of occupational/environmental or drug-related exposures, or manifestation of systemic illness: may need rheumatological evaluation to definitively diagnose (e.g. SS-A, SS-B, Scl-70, CK, CCP, RF, Jo, La, etc.). Consider Rheumatology consultation and may need hand films to help with diagnosis.

- If Chest Radiology finds usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern (e.g. honeycombing, reticular opacities, lobar volume loss, etc.) AND there is no evidence of other causes in step 1, may be sufficient to diagnose as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) without a lung biopsy.

- If no known causes as in Step 1, and imaging not conclusive for UIP pattern, may need surgical lung biopsy.

- Pulmonary function tests: restrictive lung disease with abnormal gas exchange (decreased DLCO and PaO2).

- CXR: bilateral diffuse interstitial opacities, early imaging may be very subtle.

- High-resolution chest tomography (HRCT) with expiratory and prone imaging: important role in separating patients with IPF from non-IPF ILD. IPF features include patchy, predominantly basilar, sub-pleural reticular opacities with traction bronchiectasis and honeycombing but no ground glass opacities.

- Laboratory evaluation: CBC with differential, BMP, LFTs, UA with microscopy, and CK. Additional work-up may include HIV, RF, anti-CCP, ANA, ANCA, anti-topoisomerase, anti-Scl-70, and myositis panel. ESR and CRP are nonspecific and usually not helpful in diagnosis.

Etiologies

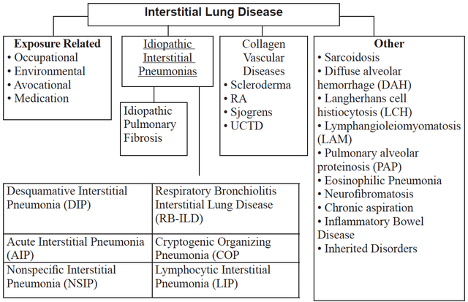

- ILDs can be classified as having known (e.g., environmental exposure) and unknown (e.g., idiopathic interstitial pneumonia) causes.

- Environmental and occupational exposures:

- Inorganic dust: asbestos, silica, beryllium, hard metals.

- Organic dust (hypersensitivity pneumonitides): thermophilic bacteria (humidifier lung, farmer’s lung), avian antigens (pigeon fancier’s lung), fungi (Aspergillus).

- Gases, fumes, vapors, including exposure to e-cigarettes/vaping.

- Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs) in order of relative frequency:

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF): unrelenting progression of disease with rare response to treatment (median survival 3 years from diagnosis; chronic duration of illness >12 months). Important to distinguish from other IIPs given its poor treatment response and morbid prognosis. Two novel therapies, pirfenidone and nintedanib, have been shown to slow disease progression in patients with mild to moderate disease, though data in patients with more advanced disease is limited.

- Steroid-responsive IIPs:

- Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP): histopathology does not fit well into established categories; course more variable than UIP and depends on degree of fibrosis. Often associated with HIV, CTD, HP, and drug exposures. Subacute to chronic.

- Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP): previously referred to as bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia (BOOP). Usually subacute (<3 months).

- Acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP): often presents as rapid progression of respiratory failure (<3 weeks) with 60% six-month mortality; usually indistinguishable from ARDS (acute hypoxemia with bilateral alveolar infiltrates). Acute.

- Respiratory bronchiolitis-associated ILD (RB-ILD): invariable relationship with smoking. Mortality is rare. Subacute.

- Desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP): also seen in smokers and typically more severe than RB-ILD, though mortality is still low. Subacute.

- Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP): associated with autoimmune diseases and HIV, female predominant. Chronic.

- Drug-related: chemotherapeutics (e.g., bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, nitrosureas, busulfan), antibiotics (e.g., nitrofurantoin, sulfonamides), amiodarone, gold. Refer to www.pneumotox.com for a comprehensive list.

- Sarcoidosis: idiopathic systemic illness characterized by granulomatous inflammation (non-caseating) in a variety of tissues with lung involvement in 90% of cases.

- CXR staging: stage I = bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (BHL); stage II = BHL with pulmonary infiltrates; stage 3 = pulmonary infiltrates without BHL; stage 4 = fibrosis.

- Steroid-responsive, with prednisone typically used as first-line therapy only in patients who are symptomatic or have evidence of end-organ dysfunction.

- Collagen vascular diseases: rheumatologic (e.g., scleroderma, polymyositis/dermatomysotis, SLE, RA), vasculitides (e.g., granulomatosis with polyangitis, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangitis, microscopic polyangitis), Goodpasture’s syndrome.

- Miscellaneous: examples include diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and eosinophilic pneumonias.

Management

- The most important distinction to make is whether the patient has IPF (as defined by the presence of UIP), as this has important therapeutic and prognostic implications (poor response to therapy and should be referred early for consideration of lung transplantation).

American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:277-304.

Collard HR, King TE. Demystifying idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:17-29.

Gross TJ, Hunninghake GW. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2001;345:517-525.

King TE. Clinical advances in the diagnosis and therapy of the interstitial lung diseases. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2005;172:268-279.

King TE, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2083-2092.

Ley B, Collard HR, King TE. Clinical course and prediction of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2011;183:431-440.

Richeldi L, Costabel U, Selman M et al. Efficacy of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1079-1087.

Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS), and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:736-755.