Risk Factors

- Age >40, prior venous thromboembolism (VTE), surgery with >30 min anesthesia, immobilization, CVA, CHF, cancer, fracture of pelvis/femur/tibia, obesity, pregnancy, estrogen therapy, inflammatory bowel disease, myeloproliferative diseases, sickle cell disease, thrombophilia.

- 20% of patients with PE have no risk factors.

Evaluation

- Clinical features:

- Symptoms: dyspnea (73%), pleuritic pain (44%), cough (37%), leg pain or swelling (44%), hemoptysis (13%), orthopnea (28%).

- Signs: tachypnea (54%), tachycardia, fever, rales, loud P2, elevated JVP.

- 97% of patients with PE will have one of the following: dyspnea, tachypnea, or pleuritic chest pain.

- Studies:

- CXR and ECG may have “classic” findings associated with PE, but both are only useful for excluding alternative diagnoses, NOT for making the diagnosis of PE.

- CXR: Westermark’s sign is a focal area of decreased pulmonary vessel perfusion; Hampton’s hump is a peripheral wedge-shaped density.

- ECG: sinus tachycardia, normal sinus rhythm, and nonspecific ST-segment and T-wave changes are the most common findings. The classic S1Q3T3, right axis-deviation, and new incomplete RBBB are less common.

- D-dimer: D-dimer tests have a strong negative predictive value for ruling out PE when clinical suspicion is low (see below). Evidence is strongest for patients in the outpatient setting or those presenting to the emergency department.

- Chest CT angiogram (contrast chest CT-PE protocol): very high sensitivity for central PE. Smaller, isolated, subsegmental PEs (frequency 1-5%) may be missed, but their significance is controversial.

- V/Q scan: alternative to CTA in the setting of renal failure; utility is limited by underlying lung pathology (COPD, pneumonia, etc.). Best study for diagnosing chronic thromboembolic disease.

- Lower extremity doppler ultrasound: in moderate or high probability patients, a positive ultrasound helps with the diagnosis of PE. If CTA is high risk due to renal failure, ultrasound can be a good alternative. It is also used to assess clot burden as a proximal clot is more likely to embolize.

- Pulmonary angiography: traditionally it was the diagnostic gold standard, now almost never performed.

- BNP/troponin for risk stratification:

- Both have good negative predictive values of death/complications.

- Elevated BNP suggests higher risk of complicated in-hospital course and death.

- Elevated troponin is associated with increased risk of death.

Approach to Suspected Pulmonary Embolism

Step 1: determine the pretest probability of PE. Consider using modified Wells’ criteria (or revised Geneva score) combined with a D-dimer test.

|

Modified Wells’ criteria |

|

|

Variable |

Point Score |

|

Clinical signs or symptoms of DVT |

3 |

|

Alternative diagnosis deemed less likely than PE |

3 |

|

HR > 100 |

1.5 |

|

Immobility (>3d) or surgery within previous 4 weeks |

1.5 |

|

Prior DVT or PE |

1.5 |

|

Hemoptysis |

1 |

|

Cancer (receiving treatment, treated in past 6 months, or palliative) |

1 |

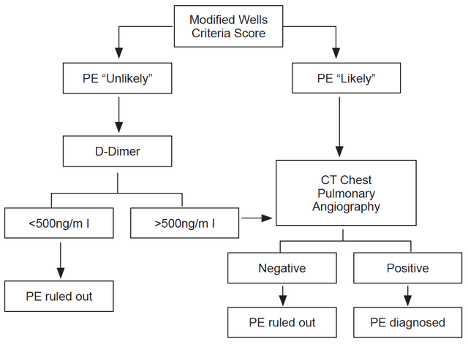

Step 2: apply score to the algorithm below:

- PE is “unlikely” if point score ≤4. PE is “likely” if point score >4.

- Note: use age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff levels (age x 10µg/L for patients >50 years) to increase the number of patients in whom PE can be excluded without increase in the rate of VTE events.

- In a large, multicenter trial (PIOPED II study) prospectively evaluating the algorithm above (605 inpatients, 2701 outpatients), the risk of venous thromboembolic events during 3-month follow-up:

- “Unlikely” + negative D-dimer = 0.5% (95% CI 0.2%-1.1%).

- “Likely” + negative CT angiogram = 1.3% (95% CI 0.7%-2.0%).

- Consider further evaluation by either V/Q scan or lower extremity doppler ultrasound in situations where pretest probability is high (Wells’ criteria score of >6) & CTA is nondiagnostic.

Management

Risk stratification

- Tools such as the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (PESI) or the Hestia criteria can be used to identify patients at low-risk of 30-day mortality, and may help in distinguishing who qualifies for early discharge and outpatient treatment.

- High-risk PE is determined by the presence of right ventricular dysfunction resulting in shock or persistent hypotension. Prompt reperfusion therapy is needed.

- Imaging, along with cardiac biomarkers, to identify RV dysfunction and clinical tools like the BOVA score are useful to further stratify intermediate-risk (hemodynamically stable who do not meet low-risk criteria) patients. Although, optimal management of these patients is unclear.

Treatment

- Anticoagulation: indicated in all patients with PE regardless of risk category.

- Non-vitamin K dependent oral anticoagulants (NOACs) have been shown in non-inferiority trials to be safe and efficacious for the treatment and prevention of recurrent PE (excluding massive iliofemoral DVT and hemodynamically unstable PE); avoid in patients with significant renal insufficiency and hepatic impairment. Discuss with pharmacy to ensure that it is covered by their insurance.

- Rivaroxaban: 15mg BID for 21 days, then 20mg daily.

- Apixaban: 10mg BID for 7 days, then 5mg BID.

- Dabigatran: must initially receive at least 5 days of parenteral anticoagulant, then transition to 150mg daily.

- Edoxaban: must initially receive at least 5 days of parenteral anticoagulant, then transition to 60mg daily.

- Low molecular weight heparin (e.g., enoxaparin): enoxaparin at 1mg/kg q12h SQ. If transitioning to warfarin, continue for ~5 days until INR is therapeutic (2-3). Do not use if CrCl <30 ml/min or weight >120 kg. Consider following anti-factor Xa levels in patients at extremes of weight or with marginal renal function.

- LMWH remains the drug of choice for cancer-associated thrombus. Although NOACs are emerging as alternative agents, further validation studies are necessary.

- Unfractionated heparin: see Appendix C: Sliding Scales.

- Warfarin: start when patient is stable (which may be on admission).

- Non-vitamin K dependent oral anticoagulants (NOACs) have been shown in non-inferiority trials to be safe and efficacious for the treatment and prevention of recurrent PE (excluding massive iliofemoral DVT and hemodynamically unstable PE); avoid in patients with significant renal insufficiency and hepatic impairment. Discuss with pharmacy to ensure that it is covered by their insurance.

- Reperfusion therapy:

- Immediate systemic fibrinolysis is indicated in patients with high-risk PE unless contraindications present. Dose tPA at 100 mg IV over 2 hours. Review full thrombolysis protocol. If available, involve the Pulmonary Embolism Response Team (PERT) or consult Pulmonary and/or the ICU Triage fellow.

- Systemic fibrinolysis is not routinely recommended in patients with intermediate-risk PE. Although, these patients should be monitored closely and rescue fibrinolysis can be considered with decompensation.

- Catheter-directed pharmacomechanical techniques (catheter-directed fibrinolysis, ultrasound-assisted thrombolysis, percutaneous mechanical thrombus fragmentation, percutaneous/surgical embolectomy) are emerging and should be considered when systemic fibrinolysis is contraindicated. Consult Interventional Radiology early to discuss. Do not delay anticoagulation while discussing with IR.

- IVC filter: for patients who develop PE while adequately anti-coagulated, or in patients in whom anticoagulation is contraindicated (e.g. recent CVA, major bleeding event). Always use removable filter when possible. Not effective as long-term treatment.

Choosing wisely pearl: don’t perform CTPE to evaluate for possible pulmonary embolism in patients with a low clinical probability and negative results of a highly sensitive D-dimer assay.

Jimenez D, Aujesky D, Moores L, et al. for the RIETE Investigators. Simplification of the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index for Prognostication in Patients With Acute Symptomatic Pulmonary Embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(15):1383-1389.

Konstantinides SV, Barco S, Lankeit M, Meyer G. Management of Pulmonary Embolism: An Update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(8):976-990. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.11.061

Righini M, Van Es J, Den Exter PL, et al. Age-Adjusted D-Dimer Cutoff Levels to Rule Out Pulmonary Embolism: The ADJUST-PE Study. JAMA. 2014;311(11):1117–1124. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.2135

Rivera-Lebron B, McDaniel M, Ahrar K, et al. Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow Up of Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Consensus Practice from the PERT Consortium. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2019;25:1076029619853037. doi:10.1177/1076029619853037

Roy PM, Colombet I, Durieux P, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of strategies for the diagnosis of suspected pulmonary embolism. BMJ 2005;331:259-267.

Stein PD, Beemath A, Matta F, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with acute pulmonary embolism: data from PIOPED II. Am J Med. 2007; 120(10):871.

Stepien K, Nowak K, Zalewski J, Pac A, Undas A. Extended treatment with non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants versus low-molecular-weight heparins in cancer patients following venous thromboembolism. A pilot study. Vascul Pharmacol. 2019;120:106567. doi:10.1016/j.vph.2019.106567

Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and d-dimer. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:98-107.