Resident Editor: Kenneth Pettersen, M.D.

Faculty Editor: Nathaniel Gleason, M.D.

|

BOTTOM LINE ✔ Diagnosis relies on excellent history-taking ✔ Always get ECG and orthostatic vital signs ✔ Low risk patients (clear orthostatic or vasovagal history, age < 50, no history of CAD, no family history of sudden death, normal exam, and normal ECG) may not require admission |

Background

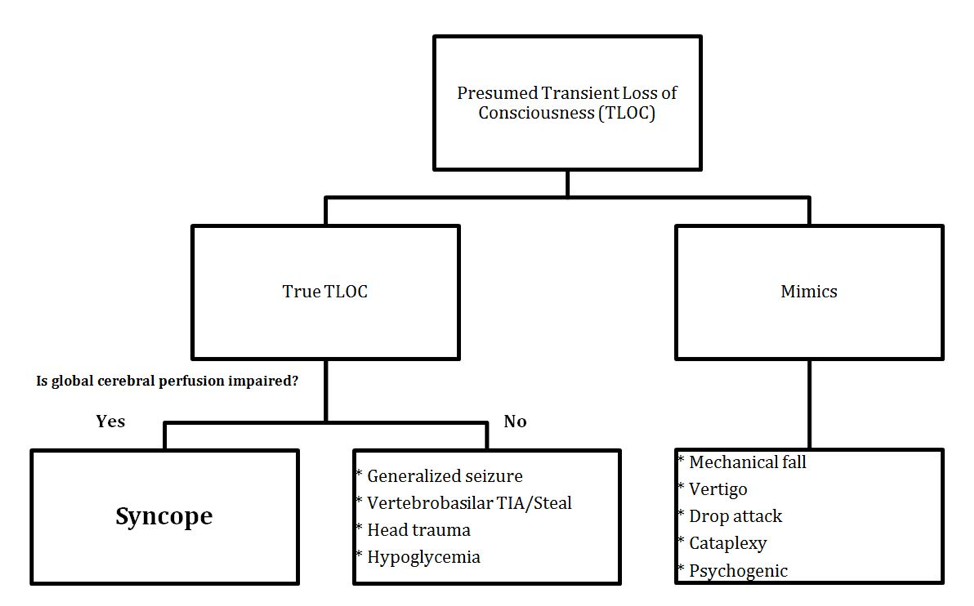

- Most common cause is syncope followed by seizure.

- Syncope – Transient loss of consciousness (TLOC) due to cerebral hypoperfusion that is self-limited and leads to loss of postural tone. Rapid onset with prompt, spontaneous, and complete recovery.

- Affects 40% of people during lifetime.

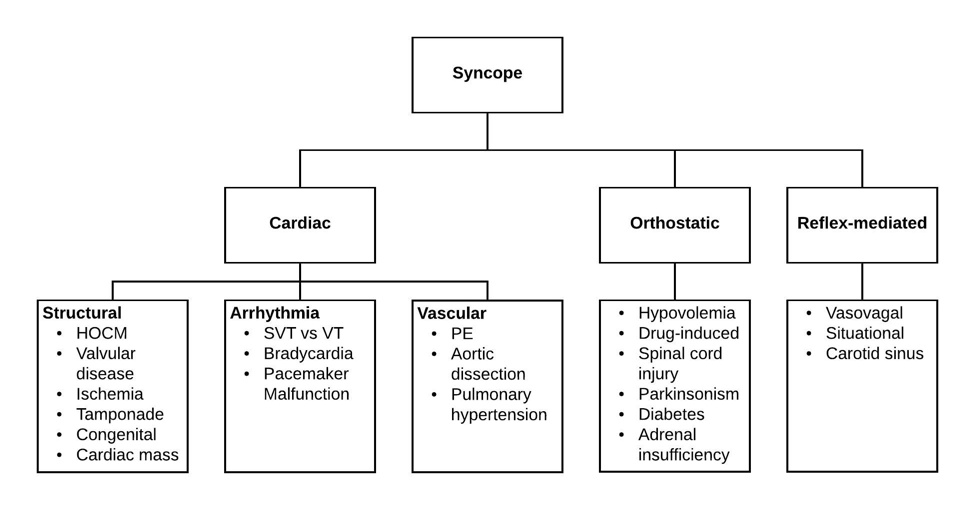

- Neurally-mediated (reflex) syncope is the most common cause, and is benign.

- Cardiac syncope must be excluded and is more common with increasing age. It is associated with increased mortality.

- TIAs do not present with TLOC unless they affect the vertebrobasilar system or bilateral cerebral hemispheres.

- The etiology is not apparent in 50% of cases.

- Near syncope can be considered in the same framework.

- Goal of evaluation is to identify etiology such that one can distinguish benign syncope from high risk causes (cardiac, non-syncope TLOC) that require specialized testing and treatment.

Evaluation

History

- Establish loss of consciousness. Assess recollection of prodrome, the event itself, and immediately following the event.

- Get collateral history from witnesses.

- Features suggestive of seizure: tongue laceration, focal movements with secondary generalization, abnormal posturing, head turning, and postictal state ;incontinence or symmetric twitching are not specific to seizure and occur in syncope as well.

- Features suggestive of non-cardiac syncope (i.e. orthostatic or reflex-mediated): presyncopal symptoms including lightheadedness, vision change, and diaphoresis.

- Orthostatic hypotension: frequently occurs when standing after prolonged sitting; common etiologies include volume depletion (GI loss, diuretics, bleeding, poor oral intake, sepsis), offending drugs (vasodilators, nodal blockers, diuretics, alcohol), autonomic failure (diabetes, spinal cord injury, parkinsonism, adrenal insufficiency).

- Reflex-mediated: assess for common etiologies, including vasovagal (emotional trigger), situational (urination/defecation, visceral pain, post-prandial, cough/sneezing), carotid sinus syncope.

- Features suggestive of cardiac syncope: LOC during/after exertion, peri-event injury, use of antiarrhythmics/anti-hypertensives/QT-prolonging meds, palpitations, chest pain, dyspnea.

- Red flags indicating need for intensive evaluation include syncope in the setting of exertion, known CAD/prior MI, heart failure, or conduction abnormality, associated chest pain, dyspnea, palpitations, and family history of sudden death.

Exam and Studies

- Orthostatics (everyone): Positive = SBP falls by ≥ 20 mmHg, or DBP falls by 10 ≥ mmHg, and/or experiencing lightheadedness or dizziness. Measure initially while supine and compare to both 1 and 3 minutes after standing (CDC definition). The earlier positive test is the strongest predictor of poor outcomes. Normally, standing leads to small fall in SBP, small rise in DBP, and moderate increase in HR (10-25 bpm).

- Pay particular attention to overall appearance, murmurs, volume status, pallor, and signs of trauma.

- Carotid sinus massage: Contraindicated if bruit is present, or if TIA/CVA in last 3 months. Has a 39% false-positive rate in older patients with no history of syncope (hence you must correlate with history).

- ECG (everyone): Look for QT prolongation, conduction disease, brady or tachy arrhythmia, presence of a pacemaker, active ischemia or old infarction, or Brugada syndrome.

- Lab tests only as indicated: Hgb/Hct in patients with hypovolemia or concern for bleeding; WBCs and lactate if septic; chemistries in patients with volume loss; troponin and ECG if concern for ischemia; d-dimer vs CTPE if concern for PE.

- Echo if concern for structural heart disease.

- Stress test vs coronary angiogram if concern for ischemia.

- Patients at risk for arrhythmia or ischemia often require 24 admission for telemetry; prolonged monitoring may be necessary if high suspicion for arrhythmia or recurrent syncope, including a holter monitor, ziopatch, or implantable loop recorder (based on frequency) if telemetry is non-diagnostic, particularly if syncope remains unexplained and patient is at high risk.

- Disposition

- Few validated clinical prediction rules exist for risk-stratifying patients with syncope.

- According to the San Francisco Syncope Rule, the presence of either CHF, Hct < 30%, abnormal ECG findings, shortness of breath, or SBP < 90 mmHg is associated with serious 30-day outcomes, and thus warrants admission. However, a meta-analysis suggests a sensitivity and specificity of 87% and 48% respectively.

- Additional risk factors include age, family history of sudden death, lack of prodrome, and other features of cardiac syncope.

Treatment

Treatment of Vasovagal Syncope, Reflex (Carotid Sinus) Syncope, and Orthostasis

- Aborting an attack:

- Sit on the floor with knees up and head between legs

- Lie with legs raised

- Isometric exercises can raise SBP (leg crossing, gluteal clenching, sustained hand grip)

- Preventing an attack:

- Drink enough fluid to keep urine clear, avoid caffeine or alcohol

- Review and minimize at-risk meds

- Use compression stockings

- For other causes of TLOC, treat underlying cause.

- DMV reporting varies by state; document that patient was counseled. Suspension of drivers license depends on the underlying cause, presence of prodromal symptoms, and severity/frequency of attacks. AHA recommendations:

- Patients with mild reflex-mediated syncope can resume private driving, while commercial drivers should be restricted for at least one month.

- Syncope without warning signs warrants suspension of private driving for at least three months and commercial driving for at least six months pending further diagnostic and management considerations.

References

Afari, ME et al. Driving Policy after Seizures and Unexplained Syncope: A Practice Guide for RI Physicians. R I Med J. 2013; January webpage: 40-43.

Gauer RL. Evaluation of Syncope. American Family Physician. 2011;84(6):640–650.

Juraschek SP, Daya N, Rawlings AM, et al. Association of History of Dizziness and Long-term Adverse Outcomes With Early vs Later Orthostatic Hypotension Assessment Times in Middle-aged Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1316–1323.

Mendu M, McAvay G, Lampert R, Stoer J, Tinetti ME. Yield of Diagnostic Tests in Evaluating Syncopal Episodes in Older Patients. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(14). 1299-1305.

Parry, SW. Current issues with prediction rules for syncope. CMAJ. 2011 Oct 18; 183(15): 1694–1695.

Parry SW, Tan MP. An approach to the evaluation and management of syncope in adults. BMJ. 2010;340(feb19 1):c880-c880.

Serrano, LA et al. Accuracy and Quality of Clinical Decision Rules for Syncope in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010 Oct; 56(4): 362–373.e1.

Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope, European Society of Cardiology (ESC), European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J 2009; 30:2631.

Thijs RD, Bloem BR, Dijk JG. Falls, faints, fits and funny turns. Journal of Neurology. 2009;256(2):155–167.