Etiology

Localizing a source of bleeding in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract can classified based on what can be visualized using different endoscopic methods.

- Upper GI bleeding (UGIB) can be defined by the GI tract that can be reached by an upper endoscopy (EGD), which can extend from the mouth to partway through the duodenum.

- Lower GI bleeding (LGIB) can be thought of as colonic bleeding, which can be evaluated by colonoscopy.

- Bleeding from for distal parts of the small bowel (e.g. the ileum) cannot be visualized by EGD or colonoscopy, and require different approaches for visualization such as capsule endoscopy or double-balloon enteroscopy; this is referred to as obscure GI bleeding.

The differential diagnosis for the source of GI bleeding can be approached by anatomic localization:

- UGIB:

- Peptic ulcer disease (~50%, H. pylori/NSAIDs/EtOH)

- Esophagitis/gastritis (~30%, GERD/EtOH/NSAIDs/infectious/pill)

- Variceal bleed (~5%, esophageal > gastric)

- Vascular lesions (~5-10%, Dieulafoy/AVM/GAVE/aortoenteric fistula)

- Traumatic (~5%, M-W tear/Boerhaave’s)

- Neoplastic (~5%)

- Post-procedural

- LGIB:

- Diverticular (30-65%)

- Ischemic colitis (5-20%), hemorrhoids (5-20%)

- Brisk UGIB (13%)

- Polyp or neoplasm (2-15%)

- Angioectasias (5-10%)

- Rare causes (<5%)

- Post-polypectomy

- IBD

- Infection

- Stercoral ulceration

- Radiation proctitis

- Rectal varices

- NSAIDs

- Dieulafoy

- Small bowel bleeds:

- 5-10% of all GI bleeds

- Suspected in cases of GI bleeding where no source identified on EGD/colonoscopy (5%)

- More common in patients <40 years old

- Tumors (e.g. lymphoma, carcinoid, hereditary polyposis)

- Meckel’s diverticulum

- Dieulafoy’s lesion

- Crohn’s disease

- Celiac disease

- More common in patients >40 years old

- Angioectasia/AVM

- NSAID enteropathy

- Celiac disease

Pre-Endoscopic Clinical Risk Stratification

Clinical judgment always comes first.

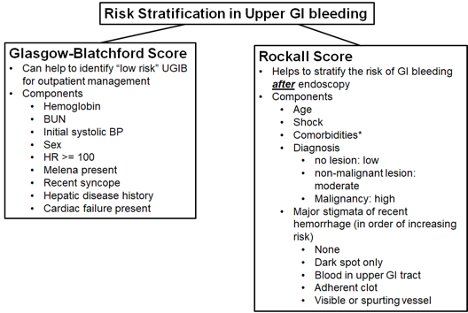

Assess the following features, based in part upon Rockall scale, BLEED criteria and Glasgow-Blatchford score. Also consider the AIMS65 to evaluate risk of mortality from UGIB.

*Major co-morbidities are defined as CAD, CHF, sepsis, altered mental status, pneumonia, COPD, asthma, etc. The higher risk co-morbidities per Rockall score are renal failure, liver disease, and disseminated malignancy.

Use clinical risk to determine urgency of endoscopy and level of care required.

Evaluation

The site of bleeding within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is only suggested by the patient’s presentation, physical examination, and laboratory data. However, below are some features commonly associated upper GI bleeding (UGIB) and lower GI bleeding (LGIB).

- History:

- UGIB: patients are more likely to report hematemesis or coffee ground emesis +/- melena (black, tarry stool).

- LGIB: patients more commonly report hematochezia (maroon or red stool).

- Note, stool color is not a reliable indicator of source as a brisk UGIB can present with hemotochezia and a lower GI bleed can present with melena (e.g., proximal/R colon source of bleeding).

- Additional historical questions:

- Current use of anticoagulation.

- History of coagulopathy.

- History NSAID or EtOH use.

- History of H pylori infection (and whether treated, and tested for cure).

- History of liver disease or known varices.

- Prior history of GI bleed.

- Prior endoscopy/colonoscopy (and if so, obtaining information on when and where was the study performed, and obtaining endoscopic reports to facilitate GI consultation).

- Recent history of severe retching.

- Prior abdominal surgery.

- History of aortic aneurysms/grafts.

- Recent trauma.

- Personal or family history of malignancy, particularly GI malignancy (also clarify age of family member at onset and side of the family, I.e. maternal or paternal).

- Physical Exam:

- Vital signs (including orthostatics).

- Abdominal exam – note any mass, peritoneal signs, ascites or stigmata of end-stage liver disease (ESLD; see below).

- Rectal exam.

- Note the color/consistency of stool (smear stool on white paper towel to see true color/content).

- Black/tarry = melena.

- Bright red blood or maroon = hematochezia.

- Stool can turn black (melena) with as little as 50-100 cc of upper GI bleeding.

- Red blood+clots has LR 0.05 for UGIB (much more likely to be lower).

- Guaiac testing is not useful for evaluation of GI bleeding; direct evaluation should be performed for signs of overt bleeding (e.g. rectal exam) prior to GI consultation.

- Examine for palpable masses or visible external anal findings (e.g., hemorrhoids, fissures).

- Note the color/consistency of stool (smear stool on white paper towel to see true color/content).

- Stigmata of ESLD (asterixis, ascites, spider angioma, palmar erythema, caput medusae, jaundice, testicular atrophy, gynecomastia); note these signs are relatively specific but not sensitive for liver disease/cirrhosis.

- HEENT: epistaxis, telangiectasias (hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias).

- NG lavage is not required for patients with upper GI bleeding. The endoscopist may use in certain patients to triage the timing of endoscopy but it should not be placed routinely. It can be helpful in patients with severe hematochezia to differentiate a brisk upper GI bleed from lower GI bleeding.

- If NG lavage is performed:

- Note amount of aspirate obtained, the quality of the aspirate, and amount of saline lavage that is required to clear it.

- The lack of blood in the NG aspirate does not rule out an upper GI bleed as it may have only sampled gastric content and bleed may be duodenal. A true negative NG aspirate is presence of clear bilious fluid (which suggests sampling of the duodenal contents).

- If NG lavage is performed:

- Laboratory data and studies:

- CBC.

- Basic metabolic panel.

- Liver chemistries.

- INR, PTT.

- Active type and screen.

- ECG for patients with a history of CAD or age > 45.

- CT AP with angiography (CTA abdomen and pelvis) should be considered in patients with signs of abdominal distension, peritonitis, obstruction, etc. or in patients who may have contraindications to endoscopy (e.g. goals of care, severe neutropenia, etc.).

- Check H. pylori serum (serum IgG, endoscopic biopsy, or stool antigen) and treat if present.

- H. Pylori diagnostic testing has higher false-negative rates in setting of bleeding and PPI use. Repeat if negative and clinical suspicion is high or treat empirically.

Management

Stabilization, resuscitation, peri-endoscopic management:

- Keep NPO until cleared by GI.

- Volume resuscitate with crystalloids.

- The goal is for patients to be well-resuscitated prior to endoscopy.

- In non-variceal upper GI bleeding, even in select high-risk patients, there is no difference in mortality among patients scoped within 6 hours from the time of GI consult vs patients scoped 6-24 hours from GI consult.

- In all patients with GIB, monitor and prepare for resuscitation with:

- Telemetry monitoring.

- Vital signs q15-30 minutes.

- 2 large bore PIVs (18g green or larger).

- Stat type and cross 2-4 U pRBC.

- Serial CBCs (often between q4h – q8hrs).

- Restrictive transfusion strategies (goal Hg>7) have been shown to be superior to more liberal transfusion strategies; may consider goal of Hg>8 for patients with CAD, particularly if there is evidence of active ischemia.

- For patients with GIB in ICU:

- Intubation may be required for airway protection in the setting of hematemesis, altered mental status, or the need for urgent upper endoscopy with a high probability of GI intervention.

- Consider cordis or rapid infusion catheter instead of triple lumen for central access.

- Acid suppression:

- Proton pump inhibitor (PPI).

- Pantoprazole 40mg IV BID or pantoprazole bolus followed by PPI infusion.

- Intermittent dosing of BID PPI is non-inferior to bolus followed by infusion.

- PPI before endoscopy does not alter mortality, re-bleed, or need for surgery however, does decrease need for endoscopic therapy and high-risk stigmata.

- Proton pump inhibitor (PPI).

- Consider surgery and/or IR consultation for severe unstable bleeding non-responsive to endoscopic therapy.

- In patients with coagulopathy:

- Hold anticoagulation in acute setting, consider reversal agents.

- Consider FFP, vitamin K (if INR >1.5), prothrombin complex concentrate (such as Kcentra to reverse AC), DDAVP (for uremic bleeding; 0.3 mcg/kg IV q12h x 3 doses), and platelets if <50. In patients with ESLD, also order fibrinogen & replete with cryoprecipitate to >100.

- Consider massive transfusion protocol if hemodynamically unstable/requiring large amount of blood products.

- Complications of massive transfusion:

- Metabolic alkalosis (due to citrate metabolism) in setting of renal impairment.

- Hypokalemia (precipitated by alkalosis).

- Hypocalcemia (due to citrate binding) - check every 4th pRBC.

- Hypothermia.

- Hyperkalemia (particularly with older blood products).

- Complications of massive transfusion:

- If a patient has re-bleeding after endoscopy for PUD:

- Preferred treatment is repeat endoscopic therapy.

- If patient has persistent bleeding after repeat endoscopy, consider CT angiogram or IR embolization.

- For uncontrolled bleeding requiring >6u pRBC there is no significant difference (rates of re-bleeding, subsequent therapy, or mortality) for IR embolization vs. surgical intervention.

- Small bowel bleeding management:

- If no source on EGD/colonoscopy and there is suspicion for active hemorrhage, video capsule endoscopy is the next study of choice for diagnostic assessment.

- Enteroscopy can be used for further evaluation of small bowel bleeding.

- Push enteroscopy – up to proximal jejunum.

- Single/double balloon enteroscopy – requires specialized gastroenterologists, can reach roughly 25% of proximal small bowel (anterograde) or 25% of distal small bowel (retrograde).

- Other diagnostic modalities (can discuss with GI first):

- Tagged RBC scan: can detect bleed rate >0.1cc/min. Localizes bleeding to area of abdomen but variable localization to portion of intestinal tract. Can re-scan several times over 24-48h after tagged RBC administration for intermittent bleeding. If positive, consider IR embolization.

- CT (mesenteric) angiography: can detect bleed rate >1cc/min.

- Low threshold to get CT Angiography and involve general surgery if there are peritoneal signs or abdominal distension; CT AP, particularly with contrast, is more sensitive for free air, perforation, or ischemia.

- Post-bleed anticoagulation/antiplatelet management:

- In resolved bleeds, patients with CAD should be continued on PPI and resumed on aspirin within 7 days.

- If ACS in past 90 days or stents in past 30, continue DAPT (discuss with GI).

- Patients with severe LGIB should not take aspirin for primary prevention.

Specific Management for Suspected Variceal Bleed

- Goal hemoglobin >7, platelets >50, INR <1.5.

- More aggressive resuscitation may result in higher rates of re-bleed due to increase in portal pressures, particularly if Hb >9.

- Do not give FFP to correct a prolonged INR in patients prophylactically, as this volume can increase portal pressure and lead to variceal hemorrhage.

- Octreotide 100 mcg bolus then 50 mcg/hr x 72 hours (constrict splanchnic circulation).

- Ceftriaxone (1gm q24h x 5 days): indicated for all types of GI bleeding with cirrhosis, reduces re-bleeding, infection, and mortality in patients with cirrhosis.

- Endoscopy fails to control bleeding in ~10-20% patients.

- Endoscopy should be within 12 hours for patients with suspected variceal hemorrhage.

- Intubation should be performed prior to EGD given high risk of aspiration.

- For persistent bleeding or re-bleed:

- Repeat endoscopic therapy.

- Balloon tamponade (e.g. Sengstaken-Blakemore tube): 50% rate of re-bleed upon balloon deflation, other complications including esophageal necrosis, rupture.

- TIPS.

- Surgery.

- Non-selective beta blockers: in combination with banding for secondary prophylaxis. Avoid with hyponatremia, AKI, SBP, diuretic resistant ascites, baseline hypotension.

- Titrate to a dose that lowers the baseline heart rate by 25% or to goal heart rate 55-60, as tolerated by the patient (15-30% of patients won’t tolerate due to low blood pressure).

- Arrange for GI follow-up (endoscopy) for serial banding.

Endoscopy

- Diagnostic and therapeutic, as well as prognostic.

- Correction of anticoagulation should not delay endoscopy.

- Would not consider unless INR >3.

Endoscopic findings used to further risk stratify patients:

|

Low Risk |

Moderate Risk |

High Risk |

|

|

|

* (risk of re-bleeding, mortality rate)

- Length of observation for re-bleeding after endoscopy depends on endoscopic and clinical risk criteria. Rapid post-endoscopy discharge is reasonable for some patients with low-risk endoscopic findings, but discuss with GI first.

Key Points

- Risk stratify patients to help determine need for endoscopy, level of care, and resuscitation needed.

- Stool is a poor indicator of source of bleeding, but can help localize.

- Critical to obtain history as most GI bleeding has precipitant.

- Early resuscitation with crystalloid is key.

Armstrong D. Intravenous proton pump inhibitor therapy: a rationale for use. Rev Gastroenterol Disord 2005;5:S18-30.

Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, Sung J, Hunt RH, Martel M, Sinclair P. International Consensus Recommendations on the Management of Patients With Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Ann Intern Med January 19, 2010 152:101-113

Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet. 2000 Oct 14; 356(9238):1318-21

Esrailian E, Gralnek IM. Nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: epidemiology and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2005;34:589-605.

Ferguson CB, Mitchell RM. Nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: standard and new treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2005;34:607-621.

Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2010 Mar 4;362(9):823-32

Gerson, LB, Fidler JL, Cave DR, Leighton JA. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Small Bowel Bleeding. AJG. 2015. 110(9):1265-87.

Green BT, Rockey DC. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding – management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2005;34:665-678.

Jensen DM, Machicado GA. Diagnosis and treatment of severe hematochezia. The role of urgent colonoscopy after purge. Gastroenterology 1988 Dec;95(6):1569-74.

Julapalli VR, Graham DY. Appropriate use of intravenous proton pump inhibitors in the management of bleeding peptic ulcer. Dig DIs Sci 2005;50:1185-1193.

Kollef MH, O'Brien JD, Zuckerman GR, Shannon W. “BLEED: a classification tool to predict outcomes in patients with acute upper and lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage,” Crit Care Med. 1997 Jul;25(7):1125-32.

Kollef MH, Canfield DA, Zuckerman GR. Triage considerations for patients with acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage admitted to a medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1995 Jun;23(6):1048-54.

Laine, L and Jensen, D. Management of Patients with Ulcer Bleeding. Am J Gastroent. 2012,107(3): 345-60

Lau, J et al. Timing of Endoscopy for Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2020 April 2; 382:1299-1308.

Raju, GS, Gerson L, Das A, Lewis B, AGA Institute Technical Review of Obscure Gastrointestinal Bleeding. November 1, 2007, Vol 133, Issue 5, p1697-1717.

Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996 Mar;38(3):316-21

SImonetto DA et al. Disorders of the Hepatic and Mesenteric Circulation. ACG Clinical Guidelines: Jan 2020;115(1):18-40

Strate LL. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2005;34:643-664.

Strate LL, Gralnek IM. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Patients with Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding. 2016. 111(4):459-474.

Villanueva C et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan 3;369(1):11-21.

Zaman A, Chalasani N. Bleeding caused by portal hypertension. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2005;34:623-642