Resident Editor: Nadine Pardee, MD

Faculty Editor: Jennifer Babik, MD

|

BOTTOM LINE ✔ Most simple abscesses in the absence of SIRS, immunocompromised status, or recurrent disease can be managed with I&D alone. ✔ If a necrotizing soft tissue infection is suspected, emergent surgical consultation warranted in addition to IV antibiotics |

Background

- The etiologic agent of a soft tissue infection depends on the epidemiologic setting and the patient’s comorbid conditions.

- It is important to obtain information about the patient’s immune status, geographical locale, travel history, recent trauma or surgery, lifestyle, hobbies, and animal exposure.

Signs and Symptoms

- An area of skin erythema, edema, and warmth, with or without an obvious site of bacterial entry. Features such as abscess, involvement of hair follicles, crusting, sharp demarcation and degree of systemic illness are key to determine the most likely inciting pathogen(s) and appropriate management.

Differential Diagnosis: Non-Purulent Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

Non-purulent Cellulitis

- Spreading skin infection that extends more deeply to involve the subcutaneous tissues. Tends to have insidious onset.

- Major pathogens: Group A streptococcus > other beta-hemolytic streptococci >>> Staphylococcus aureus

- Predisposing factors: obesity, venous insufficiency, lymphatic obstruction, trauma, preexisting skin infections, fissured toe webs from maceration or fungal infection and inflammatory dermatosis.

- Note bilateral lower extremity cellulitis is vanishingly rare. Consider venous stasis dermatitis, lipodermatosclerosis, contact dermatitis and only treat as cellulitis if high index of suspicion

- Cultures: In the absence of abscess, purulence, or severe systemic infection, limited utility (blood culture positive < 5%, punch biopsies of inflamed tissue 20-30% yield)

- Treatment:

- Limb elevation to facilitate resolution of edema

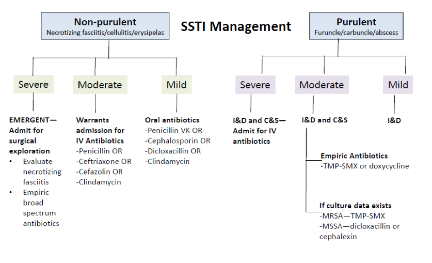

- Oral versus IV antibiotics depending on ability to tolerate PO and severity of infection (see Figure 1.).

- Cover primarily for Streptococci. Add MRSA coverage if severe infection or immunocompromised, trauma (surgery, injection drug use) or concurrent MRSA elsewhere. If purulent, see Purulent Cellulitis below.

- If perioral, orbital, or perirectal, possible connection with a pressure ulcer, surgical site infection in abdomen or axilla, prominent skin necrosis, or severe infection or immunocompromised, consider covering GNRs and anerobes with the addition of amoxicillin-clavulanate or levofloxacin and metronidazole

- Duration: For uncomplicated cellulitis a 5-day course of treatment is as effective as a 10-day course. However, if there is no improvement, longer courses of antibiotics are indicated.

- Recurrence: Manage predisposing conditions such as edema, obesity, eczema, venous insufficiency, tinea pedis or other toe web abnormalities.

- For patients who have 3-4 episodes of cellulitis per year despite management of predisposing conditions, consider oral penicillin 250 mg twice daily or IM benzathine penicillin every 2-4 weeks.

Erysipelas

- Most common in young children and older adults. Non-purulent, spreading skin infection involving the upper dermis and superficial lymphatics. Tends to have acute onset with systemic symptoms.

- Lesions are raised above the level of the surrounding skin, and there is a clear line of demarcation between involved and uninvolved tissue.

- Major pathogen: Almost always caused by group A beta hemolytic streptococci.

- Treatment: Streptococcus-active antibiotics, first choice being penicillin or amoxicillin. If staphylococcal infection is suspected, a penicillinase-resistant semisynthetic penicillin (dicloxacillin, oxacillin, nafcillin) or a first-generation cephalosporin should be selected (cephalexin). If there are systemic manifestations, IV cefazolin or ceftriaxone should be selected.

Necrotizing Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

- Deep infections involving the fascial and/or muscle compartments: Necrotizing Fasciitis, Fournier Gangrene, and Clostridial Myonecrosis

- Major pathogens:

- Monomicrobial: Streptococcus >> S. aureus (MRSA), anaerobes (Clostridia), rarely gram negatives (Aeromonas, Vibrio) OR

- Polymicrobial: mixed gram +/ gram-, aerobic/ anaerobic infection.

- Need to maintain a high index of suspicion for this life-threatening entity, as most patients are not recognized as having a necrotizing skin or soft tissue infection on admission. Clues to suggest severe deep soft tissue infection:

- Pain disproportionate to physical findings

- Violaceous bullae

- Cutaneous hemorrhage

- Skin sloughing

- Skin anesthesia

- Rapid progression

- Gas in the tissue

- Systemic toxicity (fever, leukocytosis, delirium and renal failure)

- LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indictor for Necrotizing Fasciitis): low risk (≤5 points), intermediate risk (6-7 points); and high risk (≥8 points). Initial studies showed excellent test characteristics, however subsequently demonstrated PPV of 38-85%, NPV 86-95%.

- Do not wait for a LRINEC score or be falsely reassured by a low LRINEC score: if high clinical suspicion, urgent surgical evaluation is indicated

- LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indictor for Necrotizing Fasciitis): low risk (≤5 points), intermediate risk (6-7 points); and high risk (≥8 points). Initial studies showed excellent test characteristics, however subsequently demonstrated PPV of 38-85%, NPV 86-95%.

- Treatment: suspected necrotizing soft tissue infection warrants emergent surgical consultation in addition to broad spectrum IV antibiotic therapy with Vancomycin + Clindamycin 600-900 mg IV Q8h + one of Piperacillin-tazobactam / Ertapenem / Meropenem

Differential Diagnosis: Purulent Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

Purulent Cellulitis

- See Non-Purulent cellulitis above, with the following exceptions:

- Major pathogens: Staphylococcus aureus

- Treatment: cover for Staphylococci

Abscesses

- Cutaneous abscesses are collections of pus within the dermis and deeper skin tissues, causing a fluctuant, tender, erythematous nodule

- Major pathogen: S. aureus, with MRSA accounting for a substantial proportion of these infections. May be polymicrobial, with GNRs and anaerobes more common in abscesses involving perioral, perirectal, or vulvovaginal areas and among injection drug users. Sterile abscesses may result from injected irritants

- Treatment: I&D. If complicated infection or high risk patient, may need gram stain/culture of abscess and systemic antibiotics that cover MRSA

- There is a growing body of evidence tha antibiotics improve cure rates for abscesses after I&D, but the benefit (improved cure rates of 7-14%) should be balanced against possible side effects of antibiotics.

- Daum et al. NEJM 2017: Baseline cure rate for small abscesses treated with I&D was 69-73% without antibiotics and rose to 80-83% with antibiotics

- Definitely give antibiotics if: Abscess >2-3 cm or incompletely drained, significant surrounding cellulitis (extending >5 cm from abscess), signs of systemic infection, disease at multiple sites, immunocompromised status, extremes of age, sensitive area (face, hand, genitals), or in the presence of an indwelling medical device

- There is a growing body of evidence tha antibiotics improve cure rates for abscesses after I&D, but the benefit (improved cure rates of 7-14%) should be balanced against possible side effects of antibiotics.

- Recurrence:

- If repeat abscess at same site, consider predisposing factor such as pilonidal cyst, hiradenitis suppurativa, or presence of foreign material. May require surgical exploration

Furuncle/Carbuncle

- Furuncle (“boil”) is an infection of the hair follicle which suppuration extends through the dermis into the subcutaneous tissues. Carbuncle is an infection involving adjacent follicles with coalescent inflammatory mass.

- Major pathogen: S. aureus

- Treatment:

- Small furuncles: moist heat to promote drainage.

- Larger furuncles and all carbuncles: I&D required. Antibiotics are not necessary unless fever or systemic signs of infection are present (see abscess above).

- Recurrent furunculosis: eradicate S. aureus (nasal mupirocin BID x5 days, daily chlorhexidine baths; wash towels, sheets, clothes daily)

Impetigo

- Discrete purulent lesions on exposed areas of the body (face, extremities)

- Major pathogens: S. pyogenes and/or S. aureus (bullous impetigo)

- Treatment: topical mupirocin BID (5 days) or systemic antimicrobials for multiple lesions (7 days). Dicloxacillin or cephalexin are appropriate unless MRSA is confirmed or suspected.

Evaluation

- IDSA guidelines recommend that patients with SSTI accompanied by signs of systemic toxicity (fever/hypothermia, tachycardia, hypotension) have blood drawn to classify severity of infection (blood cultures, CBC, renal panel, CPK and CRP).

- Imaging is overutilized in the evaluation of SSTIs, however it can be helpful when concerned about a necrotizing infection (see Necrotizing Skin and Soft Tissue Infections)

Treatment

- Elevation as possible for cellulitis and erysipelas

- See “Differential Diagnosis” above for indications for I&D, table below for antibiotic therapy by pathogen.

- Attention to weight-based dosing is important, particularly in obese patients who may be under dosed by standard values

![]()

Adapted from Stevens, et al, Clin Infec Dis 2014

For both purulent and non-purulent cellulitis:

- Mild: no systemic symptoms

- Moderate: may have systemic signs, but milder clinical picture than severe

- Severe: patients who have failed incision and drainage plus oral antibiotics, those with several systemic signs of infection [e.g. temperature >38°C, heart rate >90 beats per minute, respiratory rate >24 breaths per minute, white blood cell count >12 000 or <4000 cells/μL], immunocompromised patients, or those with rapid progression of erythema.

|

SSTI Pathogen |

Dosage |

Comments |

|

Streptococcus |

||

|

Amoxicillin |

500mg PO TID |

|

|

Dicloxacillin |

250mg PO QID |

|

|

Cephalexin |

500 mg PO QID |

|

|

Clindamycin |

300 mg PO TID |

|

|

Methicillin-Sensitive Staph Aureus |

||

|

Dicloxacillin |

500mg PO QID |

|

|

Cephalexin |

500mg PO QID |

Oral agent of choice for methicillin-susceptible strains |

|

Clindamycin |

300mg PO TID |

Bacteriostatic. Check biogram, increasing resistance to MSSA and MRSA. Prefer dicloxacillin or cephalexin for known MSSA. |

|

Doxycycline |

100mg PO BID |

Bacteriostatic. Poor antistreptococcal activity. Prefer dicloxacillin or cephalexin for known MSSA. |

|

TMP-SMZ |

1-2 DS tabs BID |

Bactericidal. Poor antistreptococcal activity. Prefer dicloxacillin or cephalexin for known MSSA. |

|

Cefazolin |

1 g IV q8h |

Parenteral drug of choice for treatment of infections caused by MSSA |

|

Methicillin-Resistant Staph Aureus |

||

|

Doxycycline |

100mg PO BID |

Bacteriostatic. Poor antistreptococcal activity. |

|

TMP-SMZ |

1-2 DS tabs PO BID |

Bactericidal. Poor antistreptococcal activity. |

|

Clindamycin |

300-450mg PO TID |

Bacteriostatic, inducible resistance with MRSA. Check antibiogram; increasing resistance to MSSA and MRSA. |

|

Linezolid |

600mg PO BID |

Bacteriostatic, no cross resistance with other antibiotic classes, expensive |

|

Vancomycin |

15mg/kg IV Q12 (adjust for renal fxn) |

Parenteral drug of choice for treatment of infections caused by MRSA |

When should cellulitis improve?

- Expect symptomatic improvement in 24-48 hrs, visible arrest of spread after 48-72 hrs, and closer to 72 hrs for defervescence and improved leukocytosis

- In the outpatient setting, repeat evaluation in 48 hrs to monitor clinical response

- Not improving as expected? Consider resistant organisms, deeper infection, or organism not covered by current antibiotic regimen

References

Daum et al. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Antibiotics for Smaller Skin Abscesses. NEJM 2017; 376(26): 2545-2555

Miller et al. Clindamycin versus Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole for Uncomplicated Skin Infections. NEJM. 2015; 372(12):1093-1103

Moran GJ et al. Effect of Cephalexin Plus Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole vs Cephalexin Alone on Clinical Cure of Uncomplicated Cellulitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017; 317(20):2088-2096

Stevens DL et al. Executive summary: practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infec Dis 2014:59; 147-159

Wong, CH, et al.The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2004. Jul;32(7):1535-41