Resident Editors: Sharmin Shekarchian, Allison Kwong, David Nguyen, MD

Faculty Editors: Alia Chisty, Jennifer Babik MD

|

BOTTOM LINE ✔ TB rates remain high in SF compared to the rest of the US ✔ PPD screening is for latent disease, not the active disease. Measure induration, not erythema ✔ PPD >10mm is a positive in residents of California ✔ Quantiferon test is preferred screening for latent disease in patients who have received a BCG vaccine. ✔ Positive PPD or QFTs need f/u with a CXR and ROS ✔ Consider treatment for LTBI in all patients with positive PPD or QFT ✔ Lab monitoring on treatment depends on baseline risk of liver dysfunction |

Background

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

- ~10,000 cases/year in the US, mortality in US ~4-5%

- Incidence (2016): US 2.9/100,000 (lowest in history), California 5.2/100,000, San Francisco 11.7/100,000

- In San Francisco, 88% of cases are in foreign-born individuals

- Definitions:

- Primary infection – occurs in lower lobes, middle lobes/lingula, anterior upper lobes most commonly. Hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy is common, but cavitation is rare.

- Reactivation – usually occurs in apical and posterior segments of upper lobes, superior segments of lower lobes, or other well-oxygenated areas of the body.

- Extrapulmonary disease — pleura, lymph nodes (scrofula) pericardium, spine or bone, meninges, GI tract (liver, terminal ileum, peritoneum), kidneys, retina.

- Transmitted via the airborne route

Signs and Symptoms

- Classic – fevers, night sweats, weight loss, cough, hemoptysis, loss of appetite; TB may present with non-specific pulmonary symptoms.

- In immunocompromised patients, TB can present with atypical symptoms therefore a high degree of suspicion should be maintained in high-risk patients

Evaluation

Who to screen for TB infection

- The current recommendation is for targeted skin testing of “high risk” patients only. This includes patients with conditions that increase the risk of progression from latent TB infection (LTBI) to active TB.

Table 1: Who to Screen?

|

Epidemiologic high risk |

|

|

Suspected recent infection or exposure to pulmonary or laryngeal TB Residents of high-risk congregation sites (jails, nursing homes, shelters, hospitals) Foreign-born persons from countries outside the U.S. where TB is endemic Prolonged (>1 month) or frequent travel (≥2x/year) to TB-endemic countries |

|

|

Conditions that increase the risk of progression from latent to active TB |

|

|

Organ transplant candidates/recipients HIV infection Other immunocompromised (eg chemo) Silicosis Diabetes mellitus X-ray findings consistent with prior TB Chronic renal failure/hemodialysis Cigarette smoker (≥ 1 pack/day)

|

Carcinoma of head/neck, leukemia, lymphoma Gastrectomy or jejunoileal bypass Silicosis IVDU Alcoholism On biologic agents (e.g. TNF-alpha inhibitors) Low body weight (10% or more below ideal) Systemic steroids (≥15mg/day for ≥1 month) |

|

Others |

|

|

People expected to have increased morbidity if they were to develop active TB Health care workers |

|

*Those with ongoing risk factors should get yearly TB screening (i.e. living in shelters, working in a hospital)

How to screen for LTBI

- TB Skin Test (PPD) and IGRA (IFN-gamma release assays: QuantiFERON-TB Gold, QuantiFERON TB Gold-In Tube, T-Spot TB) assays have similar sensitivity/specificity however there are some variations in numbers but generally both PPD and IGRA:

- - 80% sensitive (60% in HIV), >95% specific if no history of BCG (only 60% specific if hx of BCG)

- Most recent guidelines recommend IGRA in persons at least 5 years of age rather than PPD however PPD is an acceptable alternative, especially when IGRA is not available, too burdensome, or too costly

- While both IGRA and PPD testing provide evidence of infection, they do NOT distinguish between active or latent TB (see below)

- PPD is administered by injecting 0.1ml of 5-Tuberculin Units intradermally into the forearm using a 27-gauge needle. Discrete wheal 6-10mm in diameter should be produced. Tests should be read 48-72 h after administration by touch, not visual inspection; positive tests can remain positive for at least 5 days.

- What constitutes a positive PPD skin reaction?

- Definition of a positive PPD depends on patient characteristics (see “Interpretation of PPD” below). PPD size is based only on induration, no erythema.

- It takes 2-12 weeks after infection with MTB to develop a positive PPD.

- Note: PPD may be falsely negative in up to 25% of patients during the initial evaluation of active TB. Conditions more likely to result in a false negative: immunosuppression (TB itself, HIV, malnutrition, elderly, immunosuppressed); recent vaccination with the live-attenuated virus; improper administration; errors in reading.

Table 2: Interpretation of PPD

|

≥ 5 mm is considered positive for: |

|

Known or suspected HIV infection Recent contacts of people with active infectious (pulmonary or laryngeal) TB Fibrotic changes on chest radiograph consistent with prior TB Patients with organ transplants or other immunosuppressed patients including receiving the equivalent of >15mg/day of prednisone for > 2-4 weeks) Leukemia or lymphoma *All inmates in the California prison system (policy of the California Department of Corrections) |

|

≥ 10 mm is considered positive for: |

|

Recent immigrants from high prevalence countries (within last 5 years) Injection drug users All employees and residents of healthcare facilities People with medical conditions that increase the risk for TB disease (see table above) Infants, children, adolescents exposed to adults in high-risk categories *The California department of public health considers PPD ≥ 10mm positive, regardless of the presence of risk factors, because California is a high incidence state for TB |

|

≥ 15 mm is considered positive only for persons at the low-risk outside of California (see above) |

QuantiFERON-TB (QFT)

- IFN-gamma release assay (IGRA): similar sensitivity and specificity to PPD, more cost-effective

- QFT has the benefit of requiring a single visit and avoiding subjective reader bias

- Can still be falsely negative in immunocompromised hosts

- Previous BCG vaccination is not a contraindication to PPD testing, but quantiferon is preferred in this population due to higher specificity.

- If indeterminate, repeating QFT will result in a valid result 65-75% of the time (in San Francisco)

If active TB is suspected due to clinical symptoms or abnormal imaging, a negative PPD or IGRA cannot rule out disease and additional testing is warranted

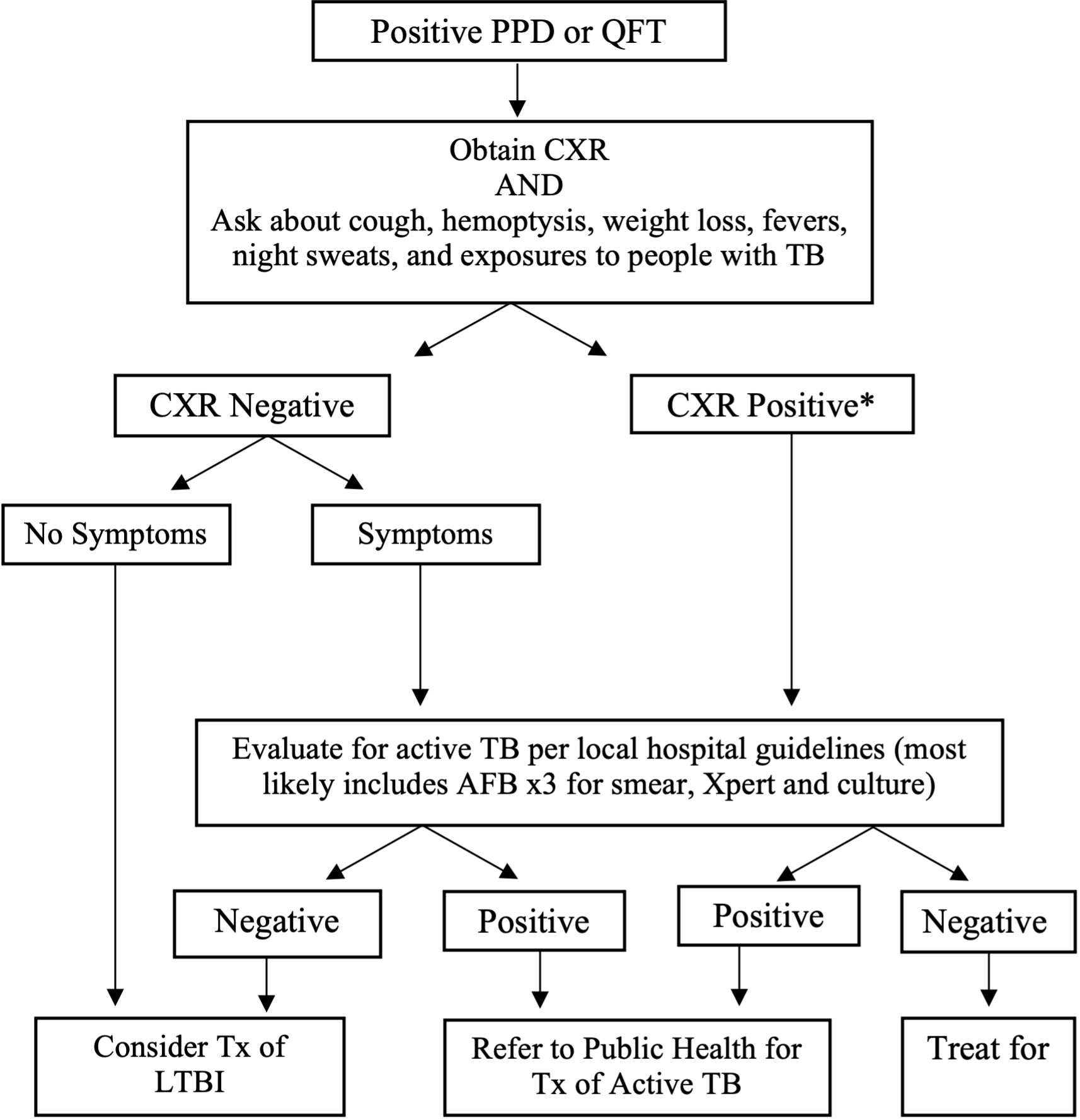

Management of Positive PPD or QFT:

*Of note, a CXR finding of “fibrotic changes consistent with old TB” is considered a positive CXR and warrants further workup

**All patients with suspected or confirmed TB infection should be reported to the Public Health Department. At UCSF, can call the City & County of San Francisco TB Control Section (415-206-8524).

Immunocompetent patients have a 5-10% lifetime chance of progressing to active TB, with half this risk concentrated in the first 2 years. Patients with HIV have a 7-10% yearly risk of active TB. Therefore, HIV patients must be treated for LTBI if indicated.

Treatment

A. Whom to treat for LTBI?

- If you are screening the appropriate population (high-risk patients), then you should recommend LTBI treatment for all patients with a positive PPD.

- Patients who are close contacts of infectious cases should be treated despite a negative PPD if they are at high risk (HIV, otherwise immunocompromised, children < 5 years)

- Recent converters, i.e. positive PPD/QFT with a documented negative result within the past 2 years

- Includes healthcare workers with conversion to positive PPD

- All patients with positive PPD and abnormal CXR (evidence of old infection) after excluding active disease.

- If cultures are obtained, do not start treatment until they are confirmed to be negative.

Who needs baseline labs before starting LTBI treatment?

- Baseline laboratory testing is not routinely indicated. Persons with the following high-risk characteristics should have baseline labs:

- HIV infection

- Intravenous drug users

- Alcohol use disorder

- Current or risk of chronic liver disease

- Women who are pregnant or within 3 months postpartum

- Those taking other hepatotoxic medications

• Which labs to order:

- Liver enzymes (AST, ALT) – for isoniazid (INH)

- CBC and liver enzymes – for rifampin or rifabutin

CDC treatment regimens for LTBI

- INH x 6-9 months (300 mg daily): Per San Francisco TB clinic guidelines, treat for at least 6 months, CDC recommends 6-9 months.

- For HIV patients or patients with fibrotic changes on CXR (old TB), treat for 9 months.

- Alternative: 900 mg twice weekly using directly observed therapy (DOT).

- Rifampin x 4 months (10 mg/kg, up to 600 mg daily): Improved rates of treatment completion and less hepatotoxicity compared to INH.

- INH + rifapentine x 3 months weekly via DOT, INH dosing is 15mg/kg, rifapentine is weight-based): Not recommended in HIV+ patients on ARVs because of drug interactions.

Vitamin B6 (25-50 mg daily) should be co-administered with INH in patients at risk for peripheral neuropathy (DM, uremia, alcoholism, malnutrition, HIV, pregnancy, elderly).

Clinical and laboratory monitoring during treatment for LTBI

- Monthly clinical evaluation for side effects, particularly hepatitis (anorexia, malaise, abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, dark urine, icterus) and for medication adherence.

- Monthly lab monitoring is indicated for the same group requiring baseline labs (see above).

- Discontinue monthly labs if LFTs WNL for > 2 months, continue monthly symptom monitoring.

- Medications should be stopped if transaminase levels > 3x the upper limit of normal (ULN) and symptomatic, or 5x ULN and asymptomatic.

- If starting rifampin, a baseline CBC is needed.

Follow-up after treatment for LTBI

- Patients with effective LTBI therapy do not need to follow up CXRs or PPDs unless they have symptoms or are re-exposed to active disease. Lifetime risk after treatment is 1.6%. Do NOT repeat PPD, it will continue to be positive.

- If patients have had inadequate LTBI therapy or refuse treatment, do an annual symptom review and risk assessment screening. Annual CXRs are NOT needed unless symptoms develop.

- For immunocompromised patients, treatment is recommended. However, if it is refused, do a symptom review every 3 months and CXR every 6 months.

B. Active TB

- Diagnosis made based on positive sputum or body fluid culture for M. tuberculosis

- Nucleic acid amplification (NAA) testing (e.g. Xpert MTB/RIF) on respiratory secretions can provide a more rapid diagnosis

- All cases of active tuberculosis must be reported, by law, to the local public health department or TB control office. In San Francisco, can call the City & County of San Francisco TB Control Section (415-206-8524).

- Isolate patient if in a congregate setting (nursing home or prison)

- An ID specialist or TB clinic should be consulted

- The classic 6-month treatment protocol includes: INH, rifampin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide x 2 months (initial phase), then INH and rifampin x 4 months (continuation phase).

- Screen for HIV; if indicated, initiate HIV treatment concurrently. Initially, may see worsening of symptoms during immune reconstitution in HIV-positive patients.

- In SF, ~9% of active TB has some drug resistance. If symptoms do not improve after 2 months and continue to have positive cultures, consider resistance (MDR/XDR TB) and send susceptibility testing

References

California Department of Public Health Annual TB Reports, 2016. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/Pages/TB-Disease-Data.aspx(accessed 3/2018)

CDC Latent Tuberculosis Infection: A Guide For Primary Health Care providers, 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/pdf/TargetedLTBI.pdf (accessed 3/2018)

CDC Treatment options for Latent TB fact sheet, http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/treatment/LTBItreatmentoptions.htm (accessed 8/2014)

Targeted Tuberculin Testing and Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2000; 161: S221-S247.

Latent Tuberculosis Infection, A Guide for Providers. Tuberculosis Control Section, SFDPH. March 2003.

San Francisco Department of Public Health Tuberculosis Control, Annual Bulletin Two-page summary of TB incidence in San Francisco (2016). https://www.sfcdcp.org/tb-control/reports-and-publications/ (accessed 3/2018)